Wild and Free

How Black Women From Southern West Virginia Shaped the 20th Century

In the 1920s, Bluefield, WV emerged as a cosmopolitan city of the highest degree. In the heart of Appalachian coal country, it was a seedbed of black entrepreneurship and empowerment. When W.E.B. Du Bois arrived to deliver a speech in Bluefield, the Bluefield Institute (now Bluefield State College, an HBCU formed in 1895) was a blossoming institution with an impressive faculty. A local black real estate developer, attorney, and West Virginia congressman, Harry Capehart, had just led the successful passage of the Capehart Anti-Lynch Law, which Historian Arthur Bunyan Caldwell called “the most progressive piece of legislation that has been enacted on the racial issue.” Residents had every reason for optimism, but I suspect that no one could have guessed the world-changing roles that local black women would soon play.

Angie Turner King was a student at the Bluefield Institute when Du Bois visited. She would go on to earn a Master’s degree in Physical Chemistry from Cornell University and a Ph.D from the University of Pittsburg. King became a teacher and passed along her passion for math and science to countless young black students including a 13-year-old Katherine Johnson whose story was told in the movie “Hidden Figures”. Johnson later taught math in a segregated school in Bluefield before she began working for NASA and helped the United States to put a man on the moon.

Du Bois’ visit to Bluefield was the first time Memphis Tennessee Garrison ever heard about the NAACP. Garrison was a brilliant teacher in a nearby community with a gift for teaching students who struggled to learn. Her research of children with developmental problems went on to be used by Columbia University while developing their special education curriculum. Garrison soon formed an NAACP chapter in her community, and within a year, she launched a Christmas Seal fundraiser out of her house. The fundraiser was so successful that it was soon adopted by the national office and became one of the NAACP’s largest, funding many of the most significant events during the civil rights movement, such as the March on Washington. Realizing what an impact the visit by Du Bois had on her, Garrison also formed the Negro Artist Series to bring the leading black entertainers, intellectuals, and political voices to the coalfields.

Through the efforts of Garrison and others, Bluefield became a hub of cultural activity. In 1930, Marian Anderson, a legendary contralto, performed at Bluefield’s Granada Theater. Marian Anderson is most famous for her Lincoln Memorial concert in 1939. She was invited to sing at Constitution Hall but was turned away by the DAR who would not let a black performer in the doors. Anderson decided to hold her performance just a few feet away on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. On Easter Sunday 1939 she sang to an integrated crowd of over 75,000 people. This was the largest crowd the Lincoln Memorial had ever seen.

Even though the Green Books (referenced below) had not been published yet, Anderson did not have to worry about finding a place to stay in Bluefield. She stayed with Mayme Wright. Mayme was the wife of the local black physician William Morris Wright, and hailed from a prominent black family from Philadelphia. (Her father had actually helped to raise money to pay for Anderson’s voice lessons when she was a child.) Her grandfather was a post-reconstruction congressman in North Carolina, her brother was a professor at Bluefield Institute, and her uncle was the President of the Medical School at Howard University. Mayme was astonishingly well connected and used her connections for the betterment of her community. Over the years, Mayme would open her home to many prominent visitors including Langston Hughes and Thurgood Marshall. Dr. Wright and Mayme had two daughters who would grow up and carry on her legacy of strength. Billie Adams, the youngest daughter, just celebrated her 92nd birthday this past weekend. Billie followed in her father’s footsteps and studied medicine at Howard University. Upon graduation, Dr. Billie Adams moved to Chicago and began to practice as a pediatrician. Over the years she would become president of the Chicago Pediatrics Society, be name Pediatrician of the Year, and become the coordinator of a medical student training program at Cook County Hospital where she would mentor and develop thousands of young physicians. As of 2019, December 12th, in the state of Illinois, is Billie Adam’s day. She is just one of the incredible black female doctors to grow up in Bluefield and shape the profession.

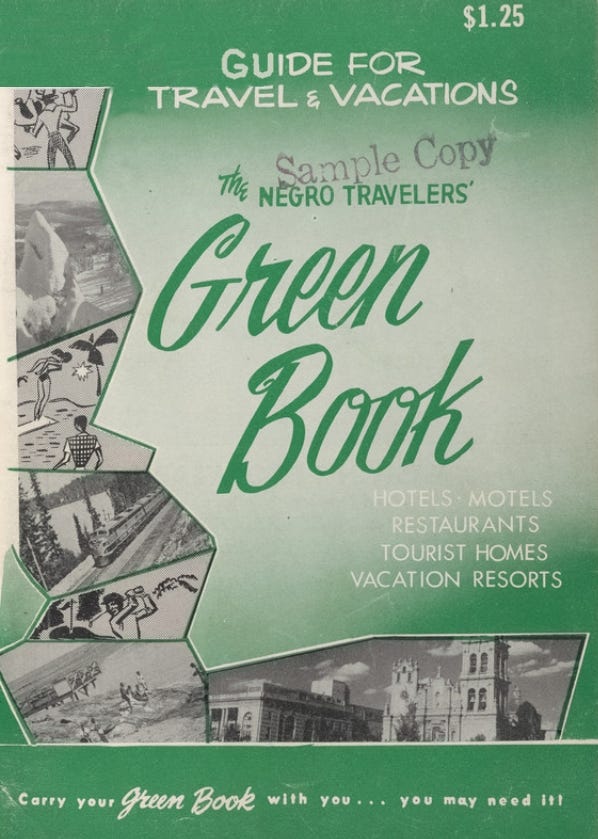

While Mayme was hosting Marian Anderson in Bluefield, Toni Stone was 9 years old. Born in Bluefield in 1921, Toni’s given name was Marcenia Lyle Stone, but all the kids called her “Tomboy.” From an early age, she loved sports and struggled in school. All she wanted to do was compete athletically. As a preteen, her family moved to St. Paul, Minnesota and Toni’s athletic abilities soon became the talk of the town. By the time she turned 16, she was getting paid to play baseball on the weekends with the Twin City Colored Giants. She eventually dropped out of high school to pursue baseball full-time. In 1949, she made history by joining the roster of the San Francisco Sea Lions. The Sea Lions were a Negro League baseball team and Toni officially became the first female to play professional sports in a men’s league. In 1953, Toni would take Hank Aaron’s spot at second base for the Indianapolis Clowns after Hank joined the Atlanta Braves. One of her crowning achievements was getting a hit off of Satchel Paige. As a member of the Negro League, Toni would have known well the struggles of travel during segregation. Not every town had a Mayme Wright.

In 1936, the first edition of the Green Book was published, and it listed all the safe hotels for blacks in cities across the country. Soon after the first publication, and with the growing number of black visitors to Bluefield, Thelma Stone, an ambitious young black woman opened up the “Hotel Thelma.” It would be a safe and hospitable place for blacks to stay when visiting this cosmopolitan city. The hotel would eventually be host to “James Brown, Little Richard (Thelma’s great-aunt Edith Morgan styled his hair), Etta James, Sam Cooke, Fats Domino, Bobby Blue Bland, and a host of other black jazz and pop musicians” including Ike and Tina Turner, who always asked for room 22. Thelma Stone also raised her great-niece Carolyn Foster Bailey Lewis in an apartment in the Hotel Thelma and passed on to her the strength and determination that had come to define the black women of Bluefield. Black Southern Belle magazine tells that Lewis “would become the first black woman to graduate with a degree in journalism from West Virginia University, the first African American woman to serve as general manager of a full-service public television station in the United States, and enjoy an illustrious career as an academic. She was also a close personal friend of the late Fred Rogers.” Thelma would go on to own two hotels in Bluefield, a grocery store, an ice cream shop, and several pieces of real estate. At a mere 5 foot 2 inches, “Mama Thelma,” as she was known, was a force to be reckoned with. https://blacksouthernbelle.com/thelma-stones-appalachian-christmas/

Even with such a distinguished legacy, Thelma was not the only black woman entrepreneur in the area, or the most successful. That title goes to Sarah Spencer Washington. Madame Washington was from nearby Beckley, WV. According to Wikipedia, she was “honored at the 1939 New York World’s Fair as one of the ‘Most Distinguished Businesswomen’ for her Apex empire of beauty company, schools, and products.” She would soon become one of the first black millionaires in America.

Bluefield also saw black women play an important role in politics. In 1928, in the nearby community of Keystone, Minnie Buckingham Harper became the first black woman legislator in the history of the United States, filling her husband's seat after his death. This accomplishment had to have inspired a young Elizabeth Simpson Drewry who would graduate from the Bluefield Institute a few years later. Drewry became the first black female elected to the West Virginia legislature and in her first term, she exposed a scandal involving attempted bribery of legislators by coal operators which won her the favor of the UMWA and guaranteed her seat for as long as she was willing to serve.

From science to sports, community activism to entrepreneurship, medicine to politics, black southern West Virginia women have played a defining role in the life of our nation and continue to do so. I am so proud to be from Bluefield. We have come a long way; we still have a long way to go. I pray our city continues to raise up Maymes and Memphis’ and Thelmas and Tonis. I pray we honor these women who broke so many barriers and whose stories have been ignored. Finally, I am grateful for current day leaders, more than I could possibly name. I am grateful for Bluefield’s own Patrice Harris, the first black woman to be named President of the American Medical Association in June of 2019, local political leaders like Barbara Thompson Smith, a former teacher and administrator who serves on our city council, and a whole host of young ambitious entrepreneurs like Jessica Bailey, who is empowering women around the country to start their own businesses.